Tallest mountain

- Who

- Mauna Kea

- What

- 10205 metre(s)

- Where

- United States (Hawaii)

- When

- 01 January 0001

Mauna Kea (White Mountain) on the island of Hawaii, USA, is the world's tallest mountain. Measured from its submarine base in the Hawaiian Trough to its peak, it has a combined height of approximately 10,205 metres (33,480 feet) of which 4,205 metres (13,796 feet) are above sea level.

Pic: Alamy

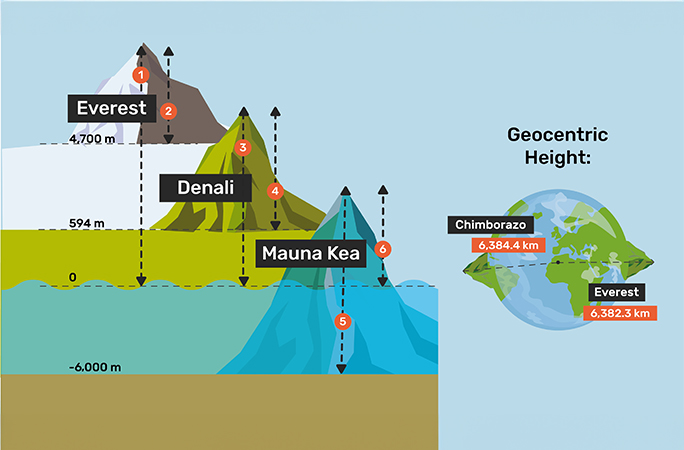

Contrary to popular belief, Everest (aka Sagarmatha; Chomolungma) in the Himalayas is not the tallest mountain in the world – though it is indisputably the highest mountain above sea level. Technically, the tallest mountain, when measured from base to tip, is the c. 10,205-m (33,480-ft) Mauna Kea (“White Mountain”) on the Big Island of Hawaii, USA. Its true magnitude is largely obscured by the fact that almost two-thirds of it lies unseen beneath the Pacific Ocean. Above the surface, it “only” rises 4,205 m (13,796 ft) – less than half the elevation of Everest.

Everest, on the other hand, soars to an unparalleled height of 8,848.8 m (29,031 ft) above sea level, cementing its reputation as the “Roof of the World” as its summit sits farthest from the planet’s surface (that is, if the ocean surface is considered 0 m).

The confusion doesn’t end there, because based on different metrics, two further mountains could be described as the biggest on Earth, and that’s before you even start talking about mountains beyond our world, but let’s focus first on Mauna Kea and Everest.

Mauna Kea

As with the entire Hawaiian archipelago, Mauna Kea formed as the result of massive volcanic activity. The area where the island group sits in the middle of the Pacific Ocean is what is known in geological terms as a “hot spot”. Here, magma from deep with the Earth rises up to the crust and regularly bursts through the seafloor atop the Pacific tectonic plate. Over millions of years, this has resulted in the creation of all the islands, atolls and reefs that make up the Aloha State.

The now-dormant Mauna Kea makes up almost a quarter of the landmass of the island of Hawaii (locally known as “Big Island”), the largest in the archipelago. Visible from everywhere on the island, it’s little wonder that the peak plays an important part in the island’s cultural identity and history, as well as its geology.

As we’ve said, the majority of Mauna Kea lies underwater, so it’s difficult to get a sense of its full height. Furthermore, there is some debate among volcanologists as to precisely where the base of Mauna Kea should be considered to begin. While most of the sea floor is between 2,500 and 3,000 fathoms (4,572–5,486 m) off the island's northern and eastern shores, and between 2,000 and 2,500 fathoms (3,657–4,572 m) to the south and west, the deepest point in the local region is a small trough called the Hawaiian Deep. In this depression, the sea floor plunges to some 3,200–3,280 fathoms (5,500–6,000 m). If the latter is considered the ultimate “base” of the mountain, and some scientists argue that case, this is how a total height of 10,205 m is arrived at.

Everest

Straddling the border of Nepal and Tibet, China, Everest is the most prominent point in the Himalayan mountain range. Although it takes the crown as the highest mountain – a title is was first bestowed in 1852, it is in good company: the Himalayas are home to nine of the top 10 highest peaks on Earth (see end for top 10).

Unlike Mauna Kea, Everest – along with the all the peaks that form the Himalayas – are not the result of volcanism, but tectonic collision. Known as “fold mountains”, this mountain system was created when the Indian Plate began to crash into the Eurasian Plate, some 50 million years ago. This convergence is still ongoing, which means that many mountains in this region – including Everest – are actually still growing.

As it isn’t static (on average rising by about 2 mm per year), pinning down a precise measurement for Everest is difficult. Based on the 1954 Survey of India, the height was confirmed to be 8,848 m (29,029 ft). In 2020, a joint expedition by Nepali and Chinese land surveyors increased its top elevation by just under a metre to 8,848.86 m (29,031 ft 8 in).

Are there any other mountains that rival Mauna Kea and Everest?

While the distinction between the tallest mountain and the highest mountain is fairly easy to grasp (at least in principle), there are some alternative approaches to assessing height that can change the record holder.

First of all, there is a measurement known as geocentric height. This is the estimated distance of between the centre of planet to the very top of a mountain. For Everest, this clocks in at an impressive 6,382.3 km (3,965,7 mi). But there is another that exceeds it: Mount Chimborazo in Ecuador is about 2 km (1.2 mi) farther from the core – 6,384.4 km (3,967 mi) to be precise. This makes it the farthest mountain peak from Earth’s centre. Or to put it another way, it is the closest that a mountain summit comes to space.

Logic might make you question how the 6,270-m-high (20,571-ft) Chimborazo could surpass the 8,848.8-m (29,031-ft) Everest, but it all comes down to their locations. The former lies just 158 km (98 mi) from the Equator at a latitude of 1.5 ° S. Everest, meanwhile, is a fair bit farther from the Equator at 27.9° N. Because our planet is not a perfect sphere – it bulges in the centre – this means that the radius from the core to the base of Chimborazo is greater by dint of it sitting on this “fatter” bit of our planet, compared to the less bulging crust between the core and the base of Everest, hence why the Andean peak beats out its Himalayan rival by this particular metric.

Another way that geographers assess a mountain’s height is topographic prominence. This is essentially the average vertical distance to a summit from its surrounding landscape. In other words, if climbing a mountain, most people wouldn’t start their journey from the nearest coast but rather the nearest relatively flat area – so in practical terms, that can be deemed the mountain’s “base”, rather than sea level.

Taking Everest, although its peak extends beyond 8,800 m above sea level, the terrain in which it sits is already extremely high, owing to the tectonic buckling that has pushed up the ground. Estimates put the average “base height” on the Nepali side of Everest to be 4,200 m (13,780 ft). So if that is deducted from its total height, that leaves a prominence of “just” 4,648 m (15,249 ft). On Everest’s Tibetan side, the average base height is even higher at 5,200 m (17,060 ft) meaning that its prominence on the north face is just 3,148 m (10,328 ft). If splitting the difference between the two sides, its prominence would come to 4,148 m (13,608 ft), which is even less than the vertical extent of Mauna Kea’s above-water section.

By contrast, North America’s highest peak – Denali in Alaska, USA – tops out at 6,190 m (20,310 ft) above sea level. But because it’s surrounded by a sloping plateau, its average base-to-height distance is 5,500 m (18,045 ft), so its topographic prominence is more than 30% greater than that of Everest.

EARTH’S MEGA MOUNTAINS EXPLAINED

- 8,848.8 m (29,031 ft 8 in): the elevation of Everest’s summit above sea level, making it the world’s highest mountain

- 4,148 m (13,608 ft): the height of Everest based on its “prominence” from the terrain that surrounds it (if averaging north and south approaches)

- 6,190 m (20,310 ft): the height of Denali above sea level, making it the highest peak in North and Central America

- 5,500 m (18,045 ft): Denali’s prominence from base to summit – more than 1.3 km (0.8 mi) greater than Everest’s

- 10,205 m (33,480 ft): the height of Mauna Kea from submarine base to snowy peak, making it the world’s tallest mountain

- 4,205 m (13,796 ft): the portion of Mauna Kea which sits above sea level is less than all of the Seven Summits (i.e., the highest individual peaks on each of the seven continents)

Can anything survive atop the world’s biggest mountains?

You might think (quite reasonably) that no creature could survive the extreme cold, low-oxygen levels and lack of food on Earth’s loftiest peaks – and in this case, we are talking specifically about mountains such as Everest that stand more than 8,000 m (26,247 ft) above sea level, rather than those with relatively much lower summits, such as Mauna Kea. There’s a good reason that anything standing above the 8,000-m mark is known as the “Death Zone”.

While it’s true that beyond 8,000 m, it’s unlikely you’ll see many creatures, one you might spot on climbing Everest is the alpine chough (Pyrrhocorax graculus), the highest-living bird. This red-legged, yellow-beaked species of corvid (the crow family) habitually lives and breeds at altitudes of up to 6,500 m (21,325 ft) above sea level, but specimens have been recorded by mountaineers scavenging as high as 8,235 m (27,018 ft).

A little farther down, it may be possible to spot the highest-living spider – the Himalayan jumping spider (Euophrys omnisuperstes), whose scientific name aptly translates as “highest of all”. In 1924, naturalist R W G Hingston collected specimens of this arachnid at a height of 6,700 m (21,982 ft); they were living under stones frozen to the ground on Everest’s upper slopes.

Away from the Himalayas, the highest-living mammal observed to date was a Phyllotis vaccarum leaf-eared mouse collected at the summit of Volcán Llullaillaco, 6,739 m (22,110 ft) above sea level in the Puna de Atacama region of northern Chile in February 2020. Image courtesy of Marcial Quiroga-Carmona

Image courtesy of Marcial Quiroga-Carmona

Who were the first people to scale Everest and Mauna Kea?

Understandably given the huge – and potentially deadly – challenges that scaling them present, it is only relatively recently that humans have found a way to conquer the full extent of these two monumental mountains.

For Everest, the breakthrough came at 11:30 a.m. on 29 May 1953, when Edmund Percival Hillary (New Zealand) and Tenzing Norgay (India/Tibet) – on an expedition led by Henry Cecil John Hunt (UK) – became the first human beings to stand atop the summit. The first female mountaineer to successfully top Everest would not come until more than two decades later, when Japan’s Junko Tabei ended her ascent on 16 May 1975.

Despite the potentially mortal risks presented by the scaling of Everest, hundreds of people are drawn here every year to climb it – so much so that there are now calls to put a cap on visitor numbers. On 23 May 2019, an unprecedented 354 people pushed for the summit in a single day.

The people to have climbed it the most are both Nepali citizens who have worked as mountain guides for many years. Fifty-four-year-old Kami Rita Sherpa has reached the top of Everest 30 times as of 22 May 2024. While the current female record is 10 ascents by Lhakpa Sherpa, her most recent Everest expedition completed on 12 May 2022; Lhakpa was the first ever Nepali woman to successfully ascend and descend her country’s treasured natural wonder (its Nepali name of Sagarmatha roughly translates as “Goddess of the Sky”).

For the less challenging Mauna Kea, indigenous Hawaiians have been scaling it for centuries – or at least those that were deemed worthy. Traditionally, the mountain claims a sacred place in local folklore – seen as both a home to the gods and a meeting point between heaven and Earth – and so historically climbing it was reserved only for elite figures such as priests and tribal chiefs; everyday people were for a long time forbidden from even venturing near it.

While it is still regarded as a spiritual place for many Hawaiians, modernity has also made its mark – though not without controversy. A series of astronomical observatories funded by 11 different countries – in fact, the largest complex of observatories (by total mirror area) – can now be found there, with telescopes trained on the sky, scouring the cosmos.

A daring attempt to ascend from Mauna Kea’s submarine base all the way to its snow-capped top was made for the first time in 2021, by explorer Victor Vescovo and Hawaiian marine scientist Dr Clifford Kapono (both USA). Over the course of three days (1–3 February), the pair travelled from the bottom of the ocean by deep-sea submersible, paddled by canoe to shore, then ascended the above-water part by bicycle and finally foot. In total, the intrepid pair ascended a vertical elevation of 9,323 m (30,587 ft).

Above 3 images courtesy of Enrique Alvarez

Above 3 images courtesy of Enrique Alvarez

This wasn’t the first time that Vescovo had used his state-of-the-art deep-water submersible to push the boundaries of human exploration. In 2018–19, he became the first human to visit the deepest points in Earth’s oceans and he has since visited the most profound of those – the Pacific’s Challenger Deep at 10,934 m (35,872 ft) below the surface – more than any other person. He is also the first explorer in history to reach Earth’s highest and lowest points (Everest and the Challenger Deep, respectively), and to boot he has been to the North and South poles and most recently to space!

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the highest mountains on each continent?

The highest-altitude mountains on each of the seven continents are known by adventurers as the “Seven Summits”. The first ever person to complete the Seven Summits (based on the Messner list, which recognizes the highest point in Oceania as being Puncak Jaya in Indonesia, as opposed to the Bass list, which instead states Mount Kosciuszko in New South Wales, Australia) was Patrick Morrow (Canada), when he successfully scaled Puncak Jaya on 5 August 1986.

The full set of Seven Summits (according to the Messner list) are as follows:

- Asia: Everest (Sagarmatha; Chomolungma): 8,848.8 m (29,031 ft)

- South America: Aconcagua, Argentina: 6,961 m (22,838 ft)

- North America: Denali, Alaska, USA: 6,190 m (20,310 ft)

- Africa: Kilimanjaro, Tanzania: 5,895 m (19,340 ft)

- Europe: Elbrus, Russia: 5,642 m (18,510 ft)

- Antarctica: Vinson Massif, Ellesworth Land: 4,892 m (16,050 ft)

- Oceania: Puncak Jaya (aka Ngga Pulu aka Jayakusuma), New Guinea, Indonesia: 4,884 m (16,024 ft)

What are the top 10 tallest mountains in the world?

In total, there are 14 peaks on Earth that exceed the 8,000-m (26,247-ft) threshold above sea level; these are known as the “8,000ers”. The top 10 highest mountains are:

- Everest (Sagarmatha; Chomolungma): 8,848.8 m (29,031 ft), Himalayas range

- K2: 8,611 m (28,251 ft), Karakoram range

- Kangchenjunga: 8,586 m (28,169 ft), Himalayas range (between 1832 and 1852, Kangchenjunga was believed to be the world’s highest mountain)

- Lhotse: 8,516 m (27,940 ft), Himalayas range

- Makalu: 8,485 m (27,838 ft), Himalayas range

- Cho You: 8,188 m (26,864 ft), Himalayas range

- Dhaulagiri I: 8,167 m (26,781 ft), Himalayas range

- Manaslu: 8,163 m (3,092 ft), Himalayas range

- Nanga Parbat: 8,126 m (26,660 ft), Himalayas range

- Annapurna I: 8,091 m (26,545 ft), Himalayas range

What is the tallest mountain in the Solar System?

Venture beyond our planet, and the contenders to be crowned “king of the mountains” get even bigger. The tallest extraterrestrial peak we currently know of is Olympus Mons on Mars. This extinct volcano reaches a height of 25 km (15 mi) from its base, two and a half times greater in size than Mauna Kea and nearly three times higher than Everest. Despite its great height, it has a very gentle slope; indeed, it is some 20 times wider than it is tall. Space scientists have recently suggested that Olympus Mons may once have been an island, surrounded by an ocean several kilometres deep.

Which is taller, Everest or Kilimanjaro?

While Kilimanjaro is the highest mountain on the African continent, reaching 5,895 m (19,340 ft) above sea level, it falls a long way short of the world’s highest mountain: Everest stands 8,848.8 m (29,031 ft) above sea level. As such, Everest is 50% higher than Kilimanjaro.

What is the highest mountain that has ever existed on Earth?

The origins of Everest and the wider Himalayan range stretches back some 50 million years, and while this makes them relatively “young” in geological terms, that is still obviously a huge time frame for us to be able to work out if any prehistoric peaks that preceded them were ever taller. From sea level changes to ice ages and tectonic and volcanic activity, there are so many factors that could affect both a mountain chain’s rise and decline. Some have suggested that North America’s Appalachians (dating back more than 1 billion years) may have in their early days reached similar proportions to the Himalayas today. Others have hypothesized that the Scandinavian Mountains (Scandes), running down the western coast of the Scandinavian Peninsula across Norway, Sweden and Finland, may once have exceeded 10,000 m (32,800 ft) but this is largely conjecture. Today across the much-eroded mountain chain, the highest peak is the 2,469-m (8,097-ft) Galdhøpiggen in Norway.